After the massive system of the Stoics, it is a relaxation to rest in the garden where Epicurus philosophizes in private with his friends, while Zeno attracts the public crowd to the Poecile portico. Between these two minds, nothing in common except the most general traits of the era: the same detachment from the city but which, in Epicurus, does not have, as in Zeno, the counterpart of attachment to nascent empires and to cosmopolitanism, and which remains in short at the level of the old sophistic criticism; a sensualist theory of knowledge, but which is not overcome, as with Zeno, by an entire rational dialectic; the affirmation of a close connection between physics and morality, but conceived in a completely different way, since Epicurean physics is precisely made to prevent reverence of what inspired Zeno with religious respect; a great desire for moral propaganda, but which in Epicurus is exercised through chosen and tested friends: each as little writer as the other; but, while Zeno creates new words or new meanings, Epicurus, a polygraph like Chrysippus, is content with simple and neglected language.

We are, moreover, in the garden of Athens, among Greeks of good stock: Epicurus is from Athens, although he was raised in Samos; and these are also the neighboring coasts or islands of Ionia, from where the first disciples came; Lampsacus, in Troas, sends Metrodorus, Polyaenus, Leonteus, Colotes and Idomeneus; from Mytilene comes Hermarchus, the first successor of Epicurus. What a welcome must have been given to all those who were worthy of it who boasted of having begun to philosophize at fourteen and who wrote to Menoeceus: “Let the young man not wait to philosophize; that the old man does not tire of philosophizing. It is never too early or too late to take care of your soul. To say that the time to philosophize has not yet arrived or that it has passed is to say that the time to desire happiness is not yet or that it is no longer.” (1) (2)

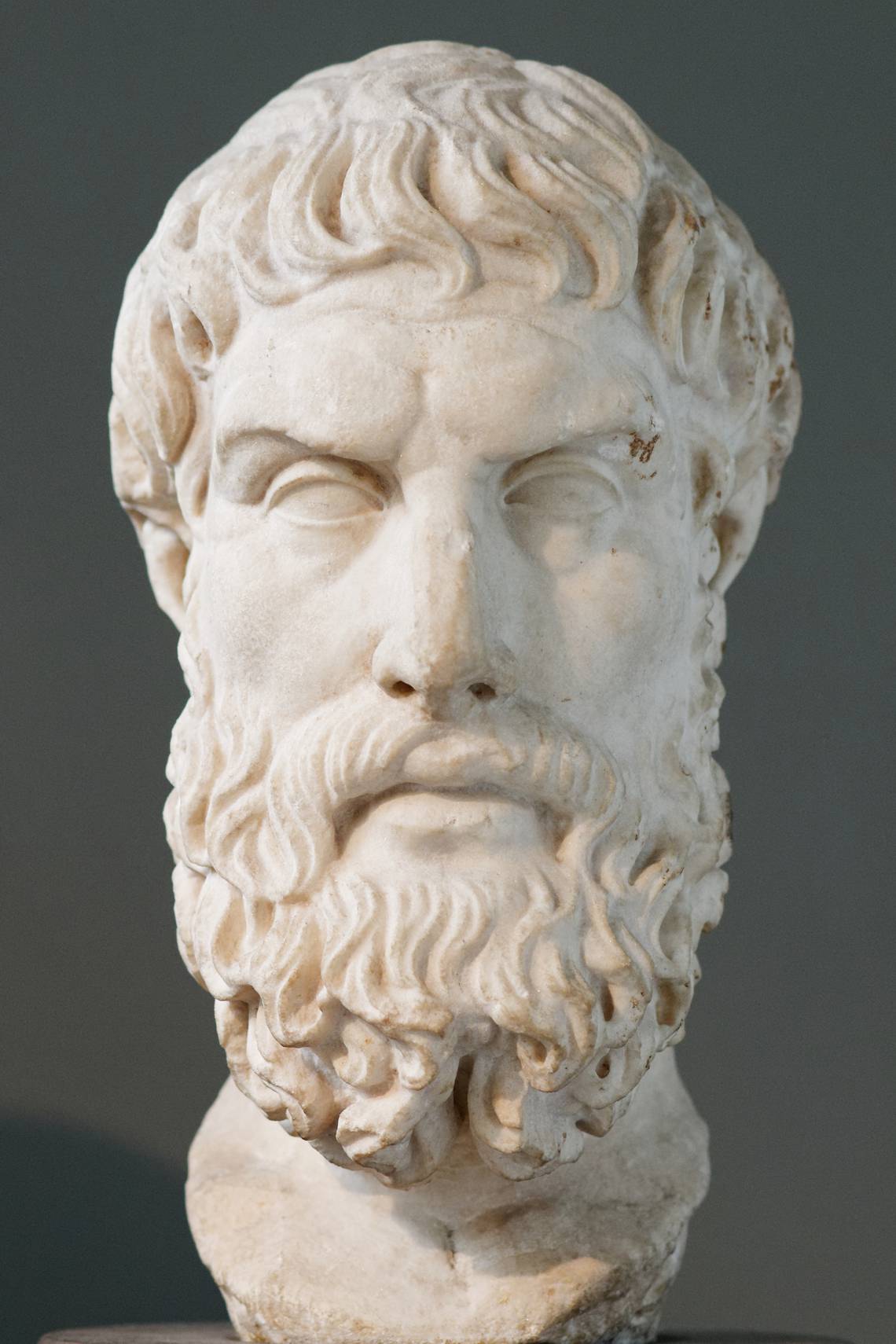

Epicurus, born in Athens in 341, spent his youth in Samos and did not return to Athens until 323; he then stayed there very little, and his retreat to Colophon, after the death of Alexander, seems to be linked to the hostility shown to him by the Macedonian masters of Athens: we now know, thanks to the research of E. Bignone, the importance of the teaching he gave at Mytilene in 310; there was a violent controversy between him and the Aristotelian Praxiphanes, who taught the first doctrine of Aristotle, that of the lost dialogues, imbued with the moral asceticism of Plato. He returned to Athens a few years later and founded school in 306, under the government of Demetrius Poliorcetes. We know the famous garden, which he bought for eighty mins, where, until his death, which took place in 270, he talked with his friends, finding in them consolation for a cruel illness which, apparently kept him paralyzed for several years. “Of all that wisdom prepares for us for the happiness of our entire life,” he wrote, thinking of this intimacy of every moment, “the possession of friendship is by far the most important.” And his will, which Diogenes Laertius has preserved for us (X, 16), shows us that he was above all concerned with maintaining this society - of which he was the soul; his executors are responsible for preserving the garden for Hermarque and all those who succeed him at the head of the school; to Hermarchus and to the philosophers of society, he bequeaths the house in which they must live together; he prescribes annual commemorative ceremonies in his honor and in honor of his already deceased disciples, Metrodorus and Polyaenus; he foresees the fate of Metrodorus' daughter, and generally recommends providing for the needs of all his disciples. From that moment onwards, Epicurean centers began to be founded in the cities of Ionia, at Lampsacus, at Mytilene and even in Egypt, and they wanted to attract the master towards them (3).

It is to this spread of the school that we undoubtedly owe the only direct documents by which we know Epicurus, three program letters containing a summary of the system, one to Herodotus on nature, the another to Pythocles on meteors, the third to Menoeceus on morality; such letters could have been written in concert with his main disciples, Hermarchus and Metrodorus, as is the case with some that we have lost (4). Besides these letters, we have the Principal Thoughts, where, in forty thoughts, Epicurus summarizes his system; To this must be added eighty-one thoughts discovered in 1888.

Such is the man with delicate health and an exquisite heart, whom his enemies represent as a debauchee and who preached the morality of pleasure in these terms: “It is not the drinks, the enjoyment of women nor the sumptuous meals that make life pleasant, it is the sober thought which discovers the causes of all desire and all aversion and which chases away the opinions which disturb the souls.” (5)

We know how much he was venerated by his first disciples, and we know the beautiful verses in which, more than two hundred years after his death, Lucretius pays homage to his genius:

“It was a god, yes a god, the one who first discovered this way of living which we now call wisdom, the one who by his art made us escape such storms and such night to place our life in a stay so calm and so bright” (V, 7).

The calm of the soul and the light of the spirit: two inseparable traits whose intimate connection makes the originality of Epicureanism. Calm of the soul can only be achieved by this general theory of the universe which is atomism and which alone makes all cause of fear and trouble disappear.

Reference

- Diogenes Laertius, X, 122.

2. Principal opinions, XXIIIÎ (USENER, Epicurea, 1887, p. 77).

3. Documents in Usener, p. 135-137.

4. A. Vogliano, “Nuovi testi epicurei”, in Ritista diJïlologia, 1926, p. 37.

5. Usener, 64, 12 ff.

Source: Émile Bréhier(1951). Histoire de la philosophie, Presses Universitaires de France. Translation and adaptation by © 2024 Nicolae Sfetcu

https://www.telework.ro/en/epicurus-and-epicureanism/

No comments:

Post a Comment